For Paul Lewis, Marc Tsurumaki and David J. Lewis, the section “is often understood as a reductive drawing type, produced at the end of the design process to depict structural and material conditions in service of the construction contract.” A definition that will be familiar to most of those who have studied or worked in architecture at some point. We often think primarily of the plan, for it allows us to embrace the programmatic expectations of a project and provide a summary of the various functions required. In the modern age, digital modelling software programs offer ever more possibilities when it comes to creating complex three dimensional objects, making the section even more of an afterthought.

With their Manual of Section (2016), the three founding partners of LTL architects engage with section as an essential tool of architectural design, and let’s admit it, this reading might change your mind on the topic. For the co-authors, “thinking and designing through section requires the building of a discourse about section, recognizing it as a site of intervention.” Perhaps, indeed, we need to understand the capabilities of section drawings both to use them more efficiently and to enjoy doing so.

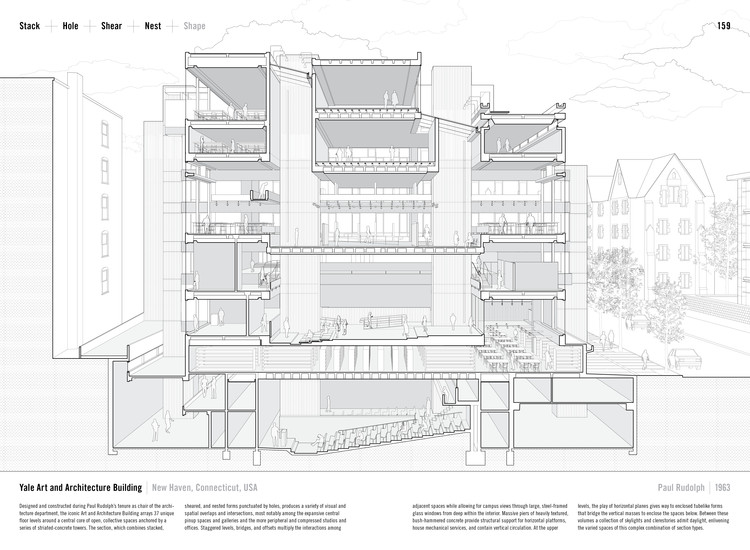

The book starts by highlighting the uniqueness of section as a representational tool. Section allows us to understand a project’s materials, structure, and tectonic logic. The vertical cut, combined with the representation of people, helps to identify scale and proportion. It simultaneously reveals a project’s neighboring urban context (the outside), its envelope and internal structure (the cut), and interior ornamental or material visual qualities (the inside). The authors also remind readers that sections and detailed sections help to solve thermal, technical and structural issues.

But the most fascinating suggestion of the text is the authors’ categorization of sections into 7 types that allow readers to engage critically with the section as a design tool. These types are “intentionally reductive” to facilitate their recognition and dissociation. “Extrusion,” “Stack,” “Shape,” “Shear,” “Hole,” “Incline,” and “Nest” each highlight a different design strategy that is exemplified by enlarged sections from well-known built projects of the 20th and 21st century. Hybrid cases are also described, showing how to combine various section types within one building. The authors manage to balance clear and informative projects with more intricate and creative ones, thus offering a good overview of section design strategy.

Interestingly, readers can assess the quality of each design in relation to vertical cuts only. The authors have avoided using plans, elevations and renders, and the use of photographs is kept to a minimum. All 63 projects are represented in one-point-perspective section, with the same standardized view and graphic representation to allow for a strictly architectural (as opposed to representational) understanding. This in turn brings complex structural systems into focus, along with sophisticated spatial hierarchies and interplays between the interior and the exterior.

The varied selection of projects is also worth noting. The book shows modernist masterpieces, such as Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame du Haut, Alvar Aalto’s Seinajoki Library, Jorn Utzon’s Bagsvaerd Church and Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art and Architecture Building, while contemporary architects featured include Toyo Ito & Associates, Sou Fujimoto Architects, OMA, Peter Zumthor, Herzog & de Meuron, MVRDV, Steven Holl Architects, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Weiss/Manfredi, BIG... the list goes on. The authors also give attention to historically significant buildings like Henri Sauvage’s social housing project 13 rue des Amiraux and Starrett & Van Vleck’s Downtown Athletic Club (later celebrated in Rem Koolhaas’ canonical text Delirious New York).

To represent these sections, the authors used an incredible amount of documentation ranging from historical photographs and detail drawings to primary documentation from contemporary architecture firms. Each section also comes with a full description, and if you’re attentive to details, you’ll even find consistency in the furniture items; don’t miss the Thonet chairs and Charlotte Perriand’s design in Le Corbusier’s work.

Finally, Manual of Section also includes a short and cohesive “History of Section” that brings perspective to the historical development and recent use of sections. The text notably sheds light on the emergence of section in the early fifteenth century, explaining how sections first appeared as an “analytical device” to depict Roman ruins. Only later did the section progressively become a “generative instrument” for architectural practice, in the works of Palladio, Etienne-Louis Boullée and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc among others.

As history shows, section has always been considered as a representational method first, and its input on architectural discourse is still largely undermined. Manual of Section successfully attempts to reintroduce sections within theoretical discourses; a new reference book for architects.

Editor's Note: this article was originally published on 16 August 2016 and updated on 27 August 2019.